What do we know about Windows 11’s security strategy?

And more importantly, will it work?

In previous posts here and here, we discussed how Macrium Reflect and Microsoft Windows 11 work together. In this article, we wanted to take a closer look at the new operating system itself, and what Microsoft’s choices indicate about their plans for what’s to come. But with many things, to get a clear picture of the future, one must briefly look at the past.

Windows 10 Vulnerabilities

BeyondTrust, a company specializing in Privileged Access Management tools, recently released their annual Microsoft Vulnerabilities Report for 2020. The results were… not great.

“A total of 1,268 were reported, which marks a colossal 48% rise over the previous year (858). This is in fact the sharpest spike since the inception of the Microsoft Vulnerabilities Report, and means that, since 2016, total vulnerabilities have increased by 181%.” — BeyondTrust

In any system, in any structure, physical or digital, you’re only as strong as your weakest link. So what doesn’t come as a surprise in their report is how a large number of these exploits could be mitigated by simply removing certain administrative privileges. People — users — will always be the weakest point. BeyondTrust goes on to say:

“90% of Critical vulnerabilities in Internet Explorer would have been mitigated through the removal of admin rights

85% of Critical vulnerabilities in Microsoft Edge would have been mitigated through the removal of admin rights

100% of all Critical vulnerabilities in Microsoft Outlook products would have been mitigated by removing admin rights”

It’s worth noting that these numbers have a double-edge. Microsoft products and services are the biggest in the market — over 1 billion people rely on Windows — making them obvious prime targets. At the same time, recognizing these exploits goes to show that the discovery and patching process is working exactly as it should. Shoring up the weakest link (users) seems to be a foundational pillar of Windows 11.

Zero Trust

Up until now, Windows has largely operated on the Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP) when it comes to administrative access. Users are granted the least amount of access as is necessary for their job. For years, Microsoft encouraged users to shore up weaknesses in their security by actively using and maintaining admin rights. It’s fundamental to proper PoLP.

PoLP has been a foundation of computer security for decades. However, to work it needs constant care and vigilance from both software developers and users to be effective. Further, it makes the assumption that the platform (OS, firmware, hardware, storage, and network) upon which the application runs is itself secure. With the increasing value of data, threats to its security and increasing use of diverse computing resources, PoLP is proving insufficient to provide protection.

Zero Trust security is similar, but not exactly the same. The idea is to never trust anyone, anything, at any time. Or, as Microsoft themselves say:

“Microsoft has adopted a modern approach to security called “Zero Trust,” which is based on the principle: never trust, always verify. This security approach protects our company and our customers by managing and granting access based on the continual verification of identities, devices and services.”

But for various reasons, users mismanage or simply don’t bother with differentiating privileges, leaving entirely preventable gaps ready for exploitation. Like a parent enforcing stricter house rules for your own good, Microsoft has stepped in.

Zero Trust policies are a new approach to secure system design that promise to deliver where PoLP cannot. In the simplest terms, it enables confidence and trustworthiness in a system to be established dynamically and continuously via a series of user and hardware verification (attestation) steps.

To execute Zero Trust verification and authentication, the platform must support a range of Trusted Computing principles to enable a verifiably secure computing, storage and networking environment. Microsoft’s approach is to utilize the same protections used to securely separate hypervisor virtual machines along with a TPM device to provide a secure host for credential storage and operations.

As an aside, DRM implementers face a challenge; they have to embed the decryption key in all devices that can play the protected content. The most celebrated attack was probably the public disclosure of the DVD encryption key. Since then, they have been an early adopter of many Trusted Computing principles. For an example, see the Protected Media Path. Trusted Computing does raise a number of ethical issues, championed notably by the EFF.

The hardware features for VBS have set the controversially high minimum hardware threshold for Windows 11. Limiting the CPU generation also eliminates a range of ‘side channel’ exploits.

To use MS nomenclature, Virtualization Based Security (VBS) provides a secure pathway in Windows 11 to implement some of the following:

- “Kernel Data Protection” enables protection from rogue kernel mode software (drivers) from compromising the Windows kernel.

- “Application Guard” utilizes VBS to isolate untrusted websites and documents and “Credential Guard” uses VBS to similarly secure access to credentials.

- “Windows Hello Enhanced Sign-In” uses VBS to create secure pathways to external components like the camera and TPM when used for authentication.

These principles extend to Microsoft’s Azure ecosystem providing remote attestation features for cloud storage and computing resources.

Microsoft is clearly making an aggressive push to set the baseline for a secure computing platform. However, it remains to be seen how quickly the industry will upgrade both its hardware and the vast base of current applications and systems to utilize modern zero trust principles and services. In the meantime threat actors will continue to target the weakest link, whether that be legacy systems, legacy applications running on modern hardware, or social engineering techniques such as BEC.

It should also be noted that bugs in hardware protections will continue to be discovered and exploited, Meltdown and Spectre being two recent examples (more about that below); it is typically more difficult or impossible to patch such issues.

From chip to cloud

In 2019, Microsoft announced Secured-core PCs as a proactive solution to growing firmware attacks, which are notoriously difficult to detect and remove.

“Secured-core PCs combine identity, virtualization, operating system, hardware and firmware protection to add another layer of security underneath the operating system. Unlike software-only security solutions, Secured-core PCs are designed to prevent these kinds of attacks rather than simply detecting them.” — Windows Blog

The concept of Zero Trust is now firmly rooted deep within the hardware of your PC, not just in the software that sits on top of it.

Windows 11 hardware requirements

Given all the above, the hardware requirements Windows 11 demands make more sense. These demands mostly likely come in no small part because of Meltdown and Spectre, two computer processor security bugs discovered in 2018.

Patrick Moorhead, president and principal analyst at Moor Insights and Strategy spoke about it in a recent article in The Verge.

“Microsoft’s CPU selections for Windows 11 don’t appear much at all to do with performance but look like security mitigations for side-channel attacks.”

The scale of these vulnerabilities honestly can’t be overstated — nearly every single device created over the span of decades was at risk. Even more, the problems were OS agnostic, but clearly Microsoft learned valuable lessons.

Welcome to the real world

Sure, Microsoft is building upon an established foundation for future security steps, but it’s almost as though they’ve ignored conditions in the real world. Some of these were unforeseen, like the pandemic and subsequent supply chain issues, but they’re huge issues to contend with nonetheless.

- Over 55% of enterprise workstations do not meet the requirements for automatic upgrades.

- Manufacturers across all industries are experiencing a global semiconductor shortage.

- Millions of perfectly good, new(ish) PCs are suddenly “obsolete,” creating untold costs and waste.

- The post-pandemic economy has not completely recovered, and many firms are still keeping a close eye on their bottom line.

Big leap? More like a small step

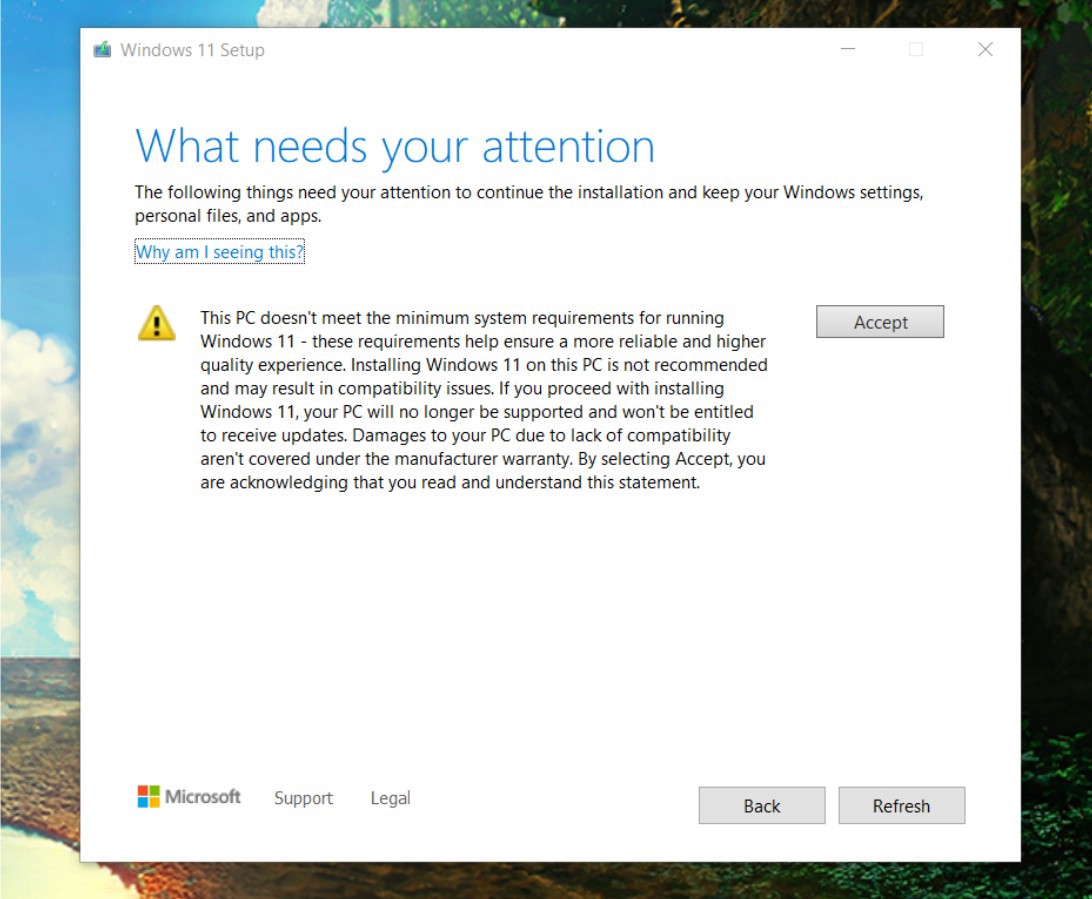

Given all these problems, it’s not surprising that Microsoft has stepped back slightly and announced that users can technically manually install Windows 11 on older PCs. As long as you have a 64-bit 1GHz processor with two or more cores, 4GB of RAM, and 64GB of storage — and you’re happy to do it — upgrading shouldn’t be a problem, even if you get some scary warnings about possible “damage” to unsupported systems. As it stands now, Microsoft will not offer updates or vital security patches to computers running Windows 11 that don’t meet the above CPU requirements.

Windows 11 upgrade warning from The Verge.

For the home and small business user who has a PC that ticks all the boxes, there is probably little practical security advantage in moving to Windows 11 at this time. The new features are either already available in Windows 10 (though not necessarily enabled by default or supported on all hardware) or only relevant in enterprise or highly secure environments. This stance may change if the Windows 11 enhanced kernel space protections prove resilient against a new class of exploit. The end of support date for Windows 10 may prove to be the biggest upgrade motivator for the security-conscious home and small business user.

What Microsoft is trying to achieve from a security perspective is commendable and certainly a move in the right direction. But considering the current issues of economic uncertainty, supply chain disruption, and the fact Windows 10 will be fully supported until 2025… it all sort of feels like much ado about nothing, for now.